Category Archives: Entertainment

My picks for the cream of the crop from WWDC 2017

Tim Cook and company introduced an unusually large number and wide array of products at this year’s WWDC — revealed in a keynote that I believe was the longest one ever delivered by Apple. Although numerous summaries of the event have been posted by now, I wanted to offer my own list of the most notable items from Apple’s latest buffet.

1. The 10.5” iPad Pro

This is the big one for me. Over the past several years, I’ve migrated from my MacBook Pro to my 9.7” iPad Pro (with keyboard and pencil). I no longer use my MacBook at all. Although I remain content with my current iPad, I’m tempted to upgrade to the newer 10.5” iPad Pro. Why? Because it offers numerous useful new features: a larger display size (while maintaining about the same dimensions overall), greater speed, better cameras, USB-3 support and (based on what I’ve read) the impressive ProMotion display.

With any iPad Pro, the machines will take another leap forward when iOS 11 comes out this fall. This update has more — and more significant — iPad-specific new features than any two previous versions of iOS combined. I’m especially looking forward to the drag-and-drop capability, the Files app (at last!) and the redesigned more flexible Dock.

The new iPad Pro is by far the closest Apple has come to a tablet that can be a viable alternative to a laptop for many people. This is the future of Apple’s mobile hardware.

But let’s not get too carried away. I confess that I’m hedging my bet here. I have a desktop iMac (which I’m using right now to write this article). I intend to keep it. Yes, my iPad Pro has replaced my MacBook, but has not yet replaced my using a Mac altogether. In that regard, my views are similar to those of Brian Chen: If you do a lot of typing, the iPad Pro is not yet ready to be your sole device. When doing work, I also prefer the larger displays, multiple windows and superior file storage options of a Mac.

2. The iMac Pro

The all new iMac Pro (touted as the most powerful Mac of any kind that Apple has ever produced) is a stunner. Unfortunately, it won’t be available until the end of the year. Even then, unless you absolutely require what it delivers, you may hesitate at the price. The Pro starts at $5000 for a base model but will go much higher for a maxed out configuration (according to one article, a top end model may go as high as $17,000). Still, I recognize that the iMac Pro is an important and lust-worthy new entry.

In many ways, the iMac Pro is the successor to the ill-fated 2013 Mac Pro. In fact, rumors indicate that, until recently, that’s exactly what Apple intended it to be. However, as we now know, a still more high-end Mac Pro (with more customization options) is due in 2018. For the pro user, this is all great news. Apple is back in the pro market — in a big way.

Also noteworthy, although far less dramatic, Apple updated its existing iMac line-up. There are upgraded internals that add speed (starting with the Kaby Lake processor), Thunderbolt 3/USB-C ports and continuing improvements to the brightness and color of the display.

I will not buying any of the new iMacs. Given my relatively modest needs, the Pro is clearly out of my price range. As for the other iMacs, I have no immediate need for Thunderbolt 3 or USB-C — and I am completely satisfied with my 2015 iMac’s speed and display. However, if you have an older iMac and have been debating getting a new one, these are the updates you’ve been waiting for.

[Note: I did buy Apple’s new extended Magic Keyboard with numeric keypad; it’s something I’d hope to see since first purchasing my iMac.]

3. HomePod

Apple’s new entry into the audio-assistant and music speaker arena, HomePod, leaves me a bit perplexed.

On the one hand, I am immensely pleased that the product exists at all (although, as with the iMac Pro, it will not ship until December). Over the past months, I have many times lamented that Apple was passing up an opportunity to compete here. With the HomePod, Apple now has at least a chance to catch up with the Amazon Echo and other entrants in this category. And HomePod appears to be a worthy entry, with high enough quality sound to make it a competitor for Sonos speakers as well as for the Echo. This has huge potential for Apple — and I hope it succeeds.

Still, HomePod is not something I intend to buy — at least not for a long while. I am already too entrenched in the Echo eco-system — and see little advantage to switching. I suspect many others are in this same position.

For top sound quality, rather than a HomePod, I much prefer my Echo Dot connected to my Yamaha soundbar (which also serves as a speaker for my TV and can connect directly to Apple devices via AirPlay). The HomePod also loses on price. At $350 each ($700 for a pair, needed for a stereo effect), it is more expensive than any Echo and/or speaker setup most buyers would otherwise consider.

Perhaps its relatively high price is why Apple chose to market the HomePod primarily as a speaker alternative, rather than as an Alexa-like assistant and a HomeKit hub. While this initially struck me as an odd marketing decision, I suspect we will see Apple tout the non-music features of HomePod much more in 2018.

4. All the rest…

Although not on a par with the big three products covered above, Apple introduced numerous other worthwhile and newsworthy items at WWDC, primarily included as part of the iOS 11 and macOS High Sierra updates coming this fall. My favorites are:

• Apple peer-to-peer payments. A Venmo competitor, this will allow you to make peer-to-peer payments via Apple’s Messages app. Could this be the tipping point for the eventual end of cash? Maybe. We’ll see.

• Safari on Mac blocks auto-play videos and ad-tracking. It’s too early to know how well this will work, but if it’s effective, it will prevent two of the most currently annoying aspects of web browsing. Here’s hoping.

• Apple File System (APFS) on macOS High Sierra. “With macOS High Sierra, we’re introducing the Apple File System to Mac, with an advanced architecture that brings a new level of security and responsiveness.” This is the first major overall to the file system since the introduction of HFS Plus almost two decades ago. With the almost total conversion to SSDs, rather than mechanical hard drives, it’s a much needed shift.

• Augmented Reality. iOS 11 will include Augmented Reality capabilities. I’m not sure how practical they will be initially, but I’m eager to try them out. In any case, it’s important for Apple to make a move in this increasingly critical area.

• Amazon on Apple TV. I prefer using Apple TV, over the numerous other options I have, for viewing Netflix and HBO GO. That’s why it’s been irritating to have to switch out of Apple TV when I want to view Amazon Prime video. No more. Amazon is coming to Apple TV this fall!

How I (almost) succeeded in getting an Echo to work well with my soundbar — and all my other components

My wife asserts that, should I die first, she will get rid of almost all the audio-video and computer equipment we now own. It’s not that she doesn’t enjoy using the equipment. She does. It’s just that she believes it will be hopeless for her to maintain the plethora of technology without my assistance.

I’m sympathetic. We currently have three TVs. Each is connected to a TiVo device, an Apple TV, a Blu-ray (or DVD) player and some sort of speaker/amplifier. Each TV setup also has its own Harmony Remote. Meanwhile, our office houses three Macs, two printers, a document scanner and a label printer. My wife and I each have our own iPhone; we share an iPad Pro. There are three Amazon Echo devices scattered about our home. Our initial foray into the world of smart home devices includes a Ring doorbell and a Nest webcam. And all of this is tied together via a complex network that employs both Wi-Fi and Ethernet.

One consequence of all of this complexity is that, anytime we add or replace a component, it may trigger a cascade of unintended and undesired consequences that can take days — or even weeks — to fully resolve.

That’s exactly what happened a few months ago — when I embarked on an “adventure” triggered by my admiration for the Amazon Echo. With the Echo linked to my Spotify account, I could speak to Alexa from almost anywhere on our main floor, request a music selection (such as “Alexa, play the Hamilton original Broadway cast album” or “Alexa, play music by Little Big Town”) and within seconds the requested music would begin. Incredible! Literally without lifting a finger, I had access to almost every recorded song in existence.

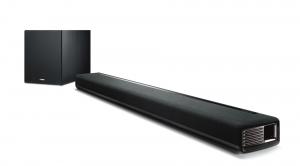

There was only one problem: the inferior quality of the sound. Don’t get me wrong. The original Amazon Echo produces surprisingly good audio for its size — better than almost any comparable small or portable speaker. But sitting just a few feet away from the Echo, connected to my TV, were a Yamaha soundbar and subwoofer capable of far better sound. I was already occasionally using the soundbar for music — via the Apple TV. But that arrangement couldn’t duplicate the “magic” of the Echo’s always-ready voice recognition.

“Wouldn’t it be great,” I mused, “if I could use the Amazon Echo for music selections and have the audio play from the soundbar? I could have my cake and it eat it too, as it were.” It sounded simple enough to do. [Spoiler alert: It’s significantly less simple than it sounds.]

A tale of two Echos and two soundbars

The first thing I realized is that the original Echo cannot connect out to a speaker — neither via a Bluetooth nor a wired connection. To do this, you need the Echo Dot. In fact, the Dot almost requires an external speaker for music (as its small internal speaker is far too weak). So I bought an Echo Dot. [Update: This limitation is now gone: All current Echoes can connect to external speakers via Bluetooth and/or wired.]

I could have connected the Dot to my soundbar via a wired connection. But I quickly dismissed this as impractical. The dealbreaker was that a wired connection totally disables the Dot’s internal speaker. This meant that I couldn’t hear any audio from the Dot — unless the Yamaha was turned on and the proper input selected (which it most often would not be). In other words, when the sound bar was off, I couldn’t use Alexa for any non-music tasks, such as asking for a weather report or setting a timer.

Connecting the Dot to the soundbar via Bluetooth seemed to offer a better chance of success — except for one thing: my 11-year-old Yamaha YSP-800 soundbar did not support Bluetooth. To use Bluetooth, I would need to get a new soundbar! I had been thinking about getting a new one anyway, for other reasons. This pushed me over the edge. After weeks of internal debate, I settled on a Yamaha YAS-706. It comes with Yamaha’s MusicCast — which provides Bluetooth, AirPlay, Wi-Fi and Internet audio options — all with access via an iOS app. The soundbar also supports every physical connection I might want (multiple HDMI ports, optical audio and coaxial audio). Quite impressive!

It took a day or two to get the new soundbar comfortably connected to all my other devices. It mostly went smoothly except for a glitch with the Harmony Remote: the remote would not reliably turn off the soundbar when doing so as part of a auto-sequence of turning off multiple devices. Consulting with Logitech, we eventually determined that the cause was the HDMI-CEC feature on the Yamaha. Disabling the option got things working pretty much as I wanted. I was now ready to make the Bluetooth connection from the Echo Dot to the new soundbar.

Initial tests of the setup were promising. The Dot was capable of turning the Yamaha on and connecting to it via a voice command — even if the speaker was presently off. And, unlike with the wired connection, there was no Input selection switching to worry about. It all just worked. And, if the Bluetooth connection was lost, the Dot would default back to its internal speaker. This was all great.

Unfortunately, a few problems persisted. First and foremost, although the setup usually worked as just described, it would fail on occasion. The causes were typically obscure — usually involving a failure to make the correct Dot-to-Yamaha Bluetooth connection. There were also occasional temporary sound dropouts. And, a couple of times, the Echo started playing music through its own speaker while I was watching TV, for no apparent reason! Without near 100% reliability, I was reluctant to commit to the Echo setup.

Second, the sound quality of the Bluetooth connection (although obviously a big improvement over any Echo speakers) was noticeably inferior to what the new soundbar was otherwise capable of producing (which I assumed was due to the sound compression used when sending music over Bluetooth). Third, the volume control on the Echo does not affect the volume setting on the Yamaha; they are separate and independent. This can require making manual adjustments to both devices to achieve a desired volume level. Ultimately, for all of these reasons, I began to consider other possible ways to use the soundbar for music.

The AirPlay and Wi-Fi alternatives

For selecting and playing music in a way similar to using Alexa, an obvious second choice is the iPhone. I could connect to the Yamaha from my iPhone via Bluetooth (which I ignored, deciding that this method belonged to the Echo), via AirPlay or via app-specific options (notably Spotify Connect — which employs a high-audio quality Wi-Fi connection). I soon settled on Spotify Connect as my preferred choice. With this, after a one time setup, I could launch the Spotify app on my iPhone and almost instantly select and play music through the soundbar. The sound quality was also superior to the Bluetooth connection.

The biggest disadvantage to Spotify Connect (and it’s a huge one) is that I can’t use voice commands to make requests. Not only can’t I request a song selection via voice, but I can’t request to pause or skip songs — as I can easily do with Alexa. An app called Melody claims to solve these issues, but it really doesn’t. As an alternative, I experimented with using Siri to control Apple Music/iTunes over AirPlay — but couldn’t get this to work to my satisfaction. The foremost problem here is that Siri sucks at this task. Too often, I had to tap an option on the iPhone screen to complete a voice request, defeating the hands-free ideal. And Siri was far worse than Alexa at correctly interpreting my requests.

However, both of these iPhone options are more convenient than my “old” method of going from my Mac to the Apple TV, as they connect directly to the soundbar, avoiding the need to turn on the television and the Apple TV. [I also like that I can set iTunes on my Mac to simultaneously play music on my Mac and directly on the Yamaha — mimicking a multi-room audio system.]

Bottom line

As of now, when listening to music, I most often use the iPhone-Spotify-Yamaha connection. It results in high quality sound with very good convenience. Or, if I want to listen to playlists in my iTunes Library, I’ll make an AirPlay connection directly from my iPhone to the Yamaha. Still, they are both a bit disappointing. My initial goal was to combine the Alexa voice interface with the Yamaha soundbar. No iPhone option is a 100% substitute for Alexa.

That’s why I continue to experiment with using the Dot-Yamaha Bluetooth connection. Most recently, by making the Yamaha the only device to which the Echo Dot is paired, I have improved the setup’s reliability. So I have begun to use it more often. As a bonus, I recently discovered that, after starting to play music from Spotify over the Echo, I can launch the Spotify app on my iPhone and modify what will play from the Echo.

[As a side note, Yamaha has announced that, sometime this fall, “MusicCast products will receive a free firmware update enabling control using Amazon’s Alexa voice service.” While I’m not exactly certain what this means, I am guessing it will permit things such as modifying the Yamaha’s volume, inputs and sound modes. But if that’s all it does, it will not significantly alter the capabilities covered here.]

All of this remains a work in progress. A final decision on a “permanent” setup may be weeks or months away. The simple truth is that the original Amazon Echo remains unmatched for its ability to instantly and reliably play music via a voice command — with decent (although not exceptional) sound quality. Nothing else I’ve tried entirely duplicates that magic. But I’m getting close.

After the Oscar boycott, then what?

Something’s rotten in Hollywood.

For the past two years, not one person of color has received an Academy Award nomination for acting. In protest, several prominent members of the film industry (including Spike Lee and Jada Pinkett Smith) have called for a boycott of the Awards ceremony.

One could make an argument that the recent nominations don’t represent a consistent bias. You could for example point out that, in the years from 2001-2006, the Best Actor award went to a person of color three times (Jamie Foxx, Denzel Washington and Forest Whitaker). During that same stretch, Will Smith, Terrence Howard, Don Cheadle and Ben Kingsley were all nominated.

But that was more the exception than the rule. There hasn’t been anything close to that ever since. While the situation may not be as dire as some suggest, I believe a problem does exist.

Even if we agree with the motivation behind the boycott, some thorny questions remain: What are people hoping to achieve by the boycott? What specific changes would be required to call off the boycott or at least not boycott again next year?

The most obvious answer seems simple enough: Have people of color get the nominations they deserve.

But it’s not quite that simple.

It’s too late to change this year’s nominations. So there’s no chance that this will end the boycott. It’s also just about impossible to imagine the Academy saying or doing anything in the next few weeks that would be radical enough to get the boycott cancelled.

So…a boycott is almost certain to happen this year. Some people will be skipping this year’s ceremony in protest.

Okay. But then what? What can be done to prevent a recurrence of the boycott next year?

Perhaps a few people of color will get nominated next year. Will that be the end of it? Maybe. But, as I’ve already pointed out, there have been years previous where people of color were nominated. That didn’t prevent what happened these past two years. So, no matter who gets nominated next year, there is no guarantee that it signals a long term shift. So what else should be done?

I doubt that anyone wants an “affirmative action” solution — one that would require a certain minimum number of people of color be nominated each year — regardless of the relative quality of their work. That would be at least as unfair as what now exists.

There is also the danger of a slippery slope here. Once you start imposing such rules, where does it stop? Many people complained that Carol did not get a Best Picture nomination this year. Speculation was that this was due to sexism — because women were in all Carol’s major roles. Is this answer here that the Academy be required to nominate at least one film that features women in the lead roles? I think not.

More generally, with Academy members voting via secret ballots, there seems no way to guarantee a desired outcome — any more than you could in a government election. The longer term solution, it seems to me, is to alter the composition of the Academy voters…which (as has been frequently pointed out) is currently made up predominantly of older white males. But this takes time, perhaps years.

Even here, a knotty problem remains. Since the Academy members are drawn from the people who do the work of making films, getting an increase in minority, female and younger members would likely require an increase in the number of those people working in films (and I don’t mean just actors here). Adding more knots, membership requires a recognition of one’s status by the very (potentially biased) people who are already in the Academy. As stated in the rules for actors as potential members:

“Membership shall be by invitation of the Board of Governors. Invitations to active membership shall be limited to those persons active in the motion picture arts and sciences, or credited with screen achievements, or who have otherwise achieved distinction in the motion picture arts and sciences and who, in the opinion of the Board, are qualified for membership.”

If the Board is biased, due in part to the current composition of its members, it will be hard for the Academy membership to change under the current rules. Perhaps there should be more objective criteria for membership, not so dependent on the “opinion of the Board.”

Still, the ultimate cause is higher up the chain. If the power structure in Hollywood is predominately white male, it likely makes it harder for people of color (and, to a similar extent, women) to achieve positions of power. This, in turn, likely makes it harder for people of color to get hired for the best acting roles. This is similar to the point that Spike Lee has made: you can’t give an award to a black person who never is given a chance to be cast in a role for which they might have won. You can’t give a Best Picture award to a movie that features black actors if that movie never gets made.

Even if you believe that the best actors this year were the ones that got nominated and there was no bias in the award selection process, the probability remains that a bias exists due to hiring decisions that trickle down from the very top.

Until the power structure in Hollywood changes, it’s difficult to see a happy ending here. Unfortunately, this is another thing that isn’t likely to happen with great haste. Many other industries, such as the tech industry (with which I am more familiar) are still struggling to resolve similar issues — such as how to get more women in positions of executive power or get jobs as entry level engineers. It hasn’t been easy.

So…by all means boycott the Academy Awards this year. But while you’re doing that, give some thought to what might realistically be done to make the situation better…so that there isn’t a reason to have another boycott next year. If you have a good idea, now’s the time to speak up.