[Yes, this is another in my continuing series of articles about the game of Letterpress. For those of you who do not play this game, feel free to move on.]

Occasionally, winning a Letterpress game requires taking a step back and rethinking your entire approach. Such was the case with a recent game of mine. Had I stuck with my typical strategies, I would have lost the game. Luckily, I became aware of the danger before it was too late. As a result, I managed to “steal” a victory—in just two moves!

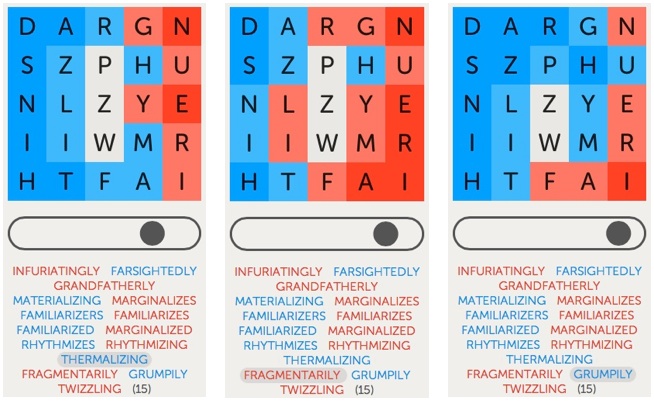

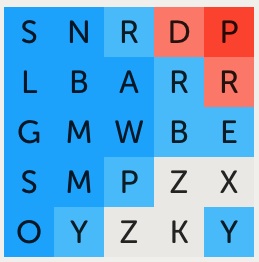

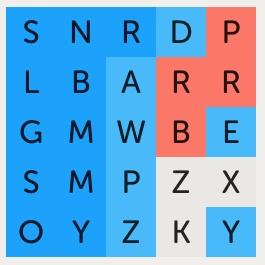

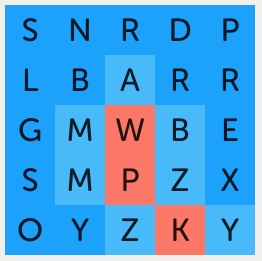

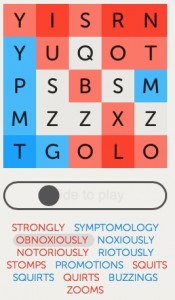

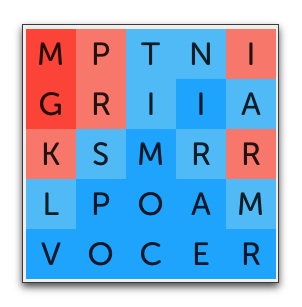

My opponent opened with the word REMARKING. Before reading further, take a moment and decide on what word you would play next.

My initial take was that I was in considerable trouble. My opponent had already protected squares in two corners—not a good sign. Worse, if I wasn’t careful, I could easily imagine him expanding to a third corner on his next turn. Alternatively, he could significantly expand his two corners at the top of the board. Either way, the game would likely be effectively over. He would be helped by the fact that the board overflowed with easy-to-find long words, such as LOVEMAKING or MISCARRIAGES or PARLIAMENTS.

I figured that, to have any chance at all, I’d have to secure both the two lower corners on my first word. Further, it would be almost as critical to simultaneously attack my opponent’s position at the top of the board. Doing all of this at once would require a fairly long word—likely 11 letters or more.

While I had no trouble coming up with 11+ letter words, none of then hit the right combination of squares. For example, OPERATIONALISM omitted the essential V, needed to grab the southwest corner. Similarly, a 15 letter word(!), IMPROVISATIONAL, amazingly did not contain an E, needed to protect the southeast corner.

Then the nickel dropped. I was looking at this game completely wrong. I was actually in much more trouble than I had realized. Paradoxically, I was also in much better shape than I had thought.

The bad news was that, even if IMPROVISATIONAL contained an E (imagine that it was spelled EMPROVISATIONAL), I couldn’t afford to play it. It would leave CMPRR as the only remaining unclaimed letters. My opponent could then play any number of possible word, such as CRIMPERS or PROCLAIMER or PARAMETRIC, and immediately win the game! Uh-oh! The same unhappy logic applied to all other super-long words I might play.

But wait! There was actually an up side to this situation. I didn’t have to play a super-long word. I didn’t even have to take both lower corners. In fact, it would be better if I didn’t. Instead, I could play a word like CARMAKERS — which is what I did.

This word secured the southeast corner, protecting three squares. More importantly, it left 11 unclaimed squares. I couldn’t be 100% certain, but I was almost sure that there was no one word that used all of these remaining letters. Even if there were, I figured it was unlikely my opponent would find it. In fact, unless he understood the situation as I now did, he probably wouldn’t even be looking for it.

For example, if my opponent came back with IMPROVISATIONAL, it would still leave one P unclaimed. That would almost certainly be sufficient for me to find a word that contained that P and enough other unprotected squares to give me a win on my next turn. Actually, my position was even better. If my opponent played any word that contained a P, other than IMPROVISATIONAL, I could play IMPROVISATIONAL and immediately win.

My opponent came back with PARKINGS. Yes! He had taken the bait and played a word with a P in it, leaving 9 unclaimed letters. He was probably feeling pretty good about his position at this point, unaware of what was about to happen.

I played IMPROVISATIONAL and “stole a win” with a score of 17-8 — ending the game with just two moves.

One final question to ponder: What should my opponent have played instead of PARKINGS?

I’m not sure. Without the help of a complete list of all possible words (that would be cheating!), he would have to be concerned that any word that took even one unclaimed square might allow me to win the game on my next turn (as, in fact, I did). Given that, it might be best for him to play a word that took no new unclaimed squares. The main exception would be if he could find a word that left him with 13 or more protected squares, blocking any chance of me winning on my next turn.

Of course, if he did play a defensive word, leaving 11 unclaimed squares, I would find myself in almost the identical dilemma. That is, both of us would likely have to play to avoid the 11 squares—and continue to do so as long as it remained a viable option. Eventually, one of us would stumble and lose. What a strange situation. But that’s what makes Letterpress such a great game.

To see a replay of the entire game, click here.

Another “stolen” victory

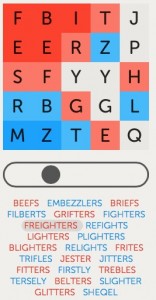

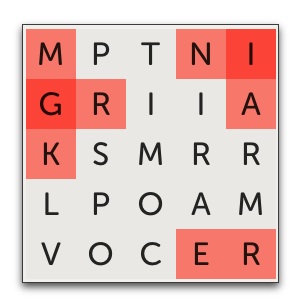

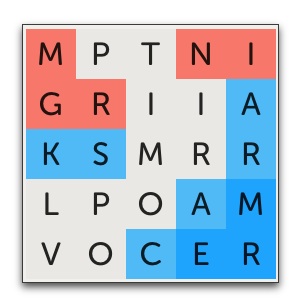

In this next game, I deliberately gave my opponent a winning position—with the hope that he would not see it. When things went as I had hoped, I was able to surprise my opponent and “steal” the victory on my next turn.

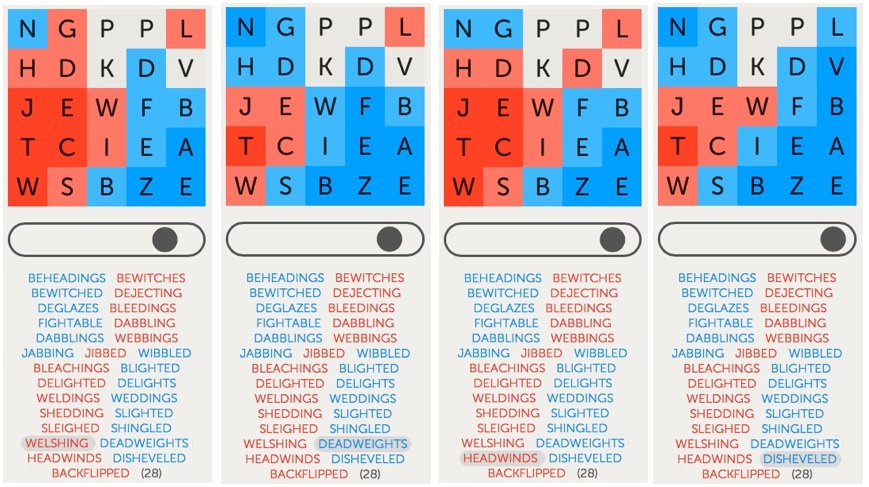

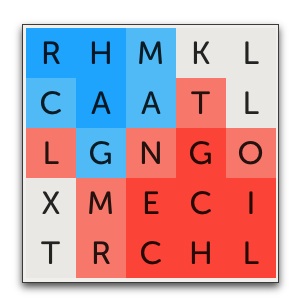

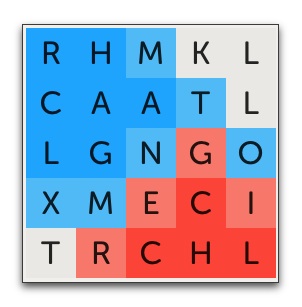

The game was hard-fought over the first eight moves. However, playing second, I was definitely on the losing end of the battle. After my opponent played MOLTEN on move 9, I was unable to see any clear path to victory.

The gist of the situation was that both of us were avoiding the 5 unclaimed squares (XTKLL) for the typical reason: there was no one word that used all 5 letters and the fear was that claiming any one of the 5 letters could allow the opponent to take the remaining 4 and win. For example, if either of us had taken the K, the other player could play EXTOLLING and win. As I recall (my memory’s a bit hazy here), it probably would have been safe to take the T in the southwest corner; however, this would have required a word with two T’s, as neither of us wanted to leave the upper T in the opponent’s hands. There weren’t many words with two T’s that also included the other required squares. ALLOTMENT was a possibility (my opponent might have played it instead of MOLTEN). As for me, I valued the R more than the second T. So the T was left alone.

As such, we were left to skirmish over the claimed but unprotected squares (LMRNTO), exchanging possession of most or all of them with each turn.

If we continued to maintain this see-saw exchange, it’s possible I would have wound up with a final advantage. But it seemed unlikely. With the advantage of having gone first, my opponent was always just a bit ahead. So, out of a sense of “desperation,” I decided to attempt a swindle and go for a quick win. I played EXCLAMATION, taking the X of the unclaimed squares.

If my opponent could now find and play a word that used KLLT, he was almost certain to win the game. Actually, I already knew there was at least one such word: CLOTHLIKE. This word would win the game for my opponent. My hope here was that my opponent would not discover this word and (incorrectly) assume he instead needed to continue the see-saw. It seemed worth a shot in a game that I was otherwise likely to lose anyway.

I got my wish. My opponent played EXAMINATOR. It was a great word, reclaiming the MNTO squares as well as taking the newly claimed X. Had I continued the see-saw, I didn’t know of any word that I could use to take back MNTOX. Most likely, I would have had to leave my opponent with the X and an increased advantage. I’m sure that’s what my opponent was expecting to happen.

Fortunately, I didn’t have to do that. Instead, I played CLOTHLIKE and stole the victory by the thinnest of margins, 13-12.

To see a replay of the entire game, click here.

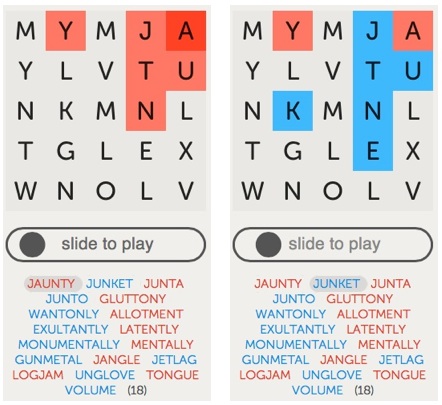

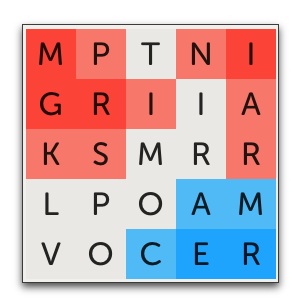

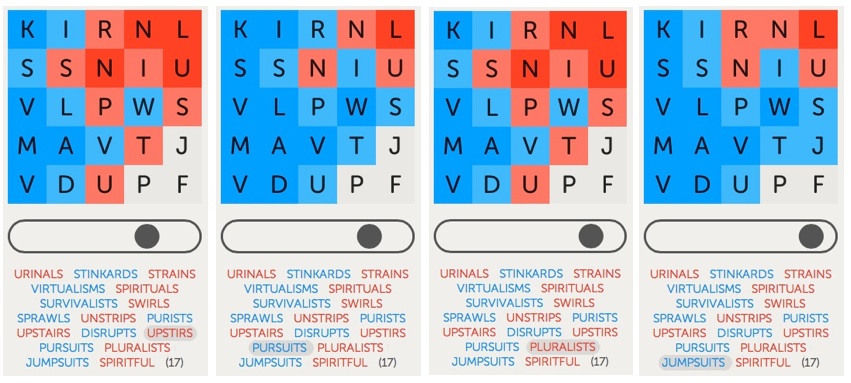

Figure 1: By playing JUMPSUITS, I got off the see-saw.

Figure 1: By playing JUMPSUITS, I got off the see-saw.