I like Letterpress. A lot. In fact, it is my favorite new game since Angry Birds. For me, it is a nearly perfect merger of my dual interests in word puzzles and strategy board games. My hat is off to developer Loren Brichter for creating this delightful app.

I’m not going to review the basics of the game here. I figure that, if you don’t already know how to play, you’re not going to be reading this article anyway. If you do prefer a review of the rules and essential strategy, I highly recommend Josh Centers’ Letterdepressed in Marco Arment’s The Magazine.

My focus here is on how to play when you go second after your opponent has made a great opening move. In this regard, Josh Centers writes:

The first move in Letterpress confers a huge advantage. A well-played opening can devastate your opponent. If you’re opening the game, always defend a corner letter and make the longest word you can.

If you play following an opponent’s really great opening, you’re at a disadvantage, but not an insurmountable one. Like Microsoft in the ’90s, you want to “embrace and extend.” “Embrace” the opponent’s letters by using as many as possible, and “extend” by using unclaimed letters, preferably taking another corner as you do so.

However, the current first-mover advantage might be short lived. Developer Loren Brichter told me that he’s considering adding a “pie rule,” which would allow the second player to veto the opening move.

While Josh acknowledges that a great opening is not an “insurmountable” advantage, it sure comes close to sounding like one. If not, Loren wouldn’t be considering a “pie rule” (which I hope he doesn’t do). While it’s certainly an advantage to go first, I wouldn’t be too concerned — no matter how big the advantage seems.

I have currently won my last 60+ games. In almost two-thirds of those games, I played second — usually after my opponent got off to a solid start. Yet, in every case, I won.

There’s no big secret to how to do this. Essentially, I followed the advice outlined in the quote above. However, going from abstract advice to practical implementation may prove a bit tricky. That’s where a game replay can help.

What follows is a move-by-move analysis of a tightly fought game, explaining the thinking and strategy that went behind each move. I also include briefer analyses of two other games. My hope is that these annotated replays can help develop your own skills.

Game 1

As the figures below do not include every move of the game, you should ideally follow along with the full replay of the game.

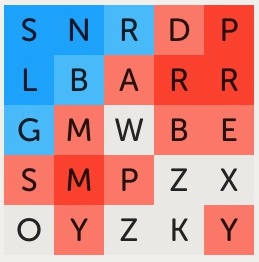

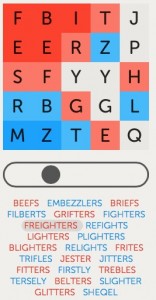

Move 1. My opponent opens with the word DRAPERY, leaving the strong position shown in the figure below.

She has solid control of the northeast corner, with two protected (dark red) squares. It’s an especially strong start because the corner contains the letters d, r and e. These are desirable letters to re-use for long words — as they form the suffixes -er and -ed. For example, you could turn a word like SLAM into (with the second M) the much better SLAMMED or SLAMMER.

After a start like this, I assume the corner (perhaps 6-8 squares) will still be in my opponent’s color at the end of the game. I may be able to do better, but I don’t count on it. The good news is that, even with the corner lost, I can still theoretically win by at least 17-8. Accomplishing this, however, will require playing catch-up for most of the game and being very careful not to make mistakes. One or two, even minor, errors can quickly turn a disadvantage into a sure loss.

Move 2. I give a great deal of thought to my first move. Unless an obviously great word presents itself, I typically spend more time on my first move than any two or three moves for the rest of the game.

When playing second, I do my best to have my move accomplish two goals simultaneously: (1) Force my opponent to defend their advantage and, if possible, (2) establish a corner of my own. Ideally, this requires my opponent to fight back on two fronts. By continuing this dual pressure over several turns, I hope to eventually build an advantage while limiting the ability of my opponent to expand their lead.

I attempted to accomplish this goal in this game with the word SLANDERS. It gave me the desired foothold in the northwest corner plus turned every light red square in the northeast corner to blue. Perfect!

Moves 3-5. My opponent came back with BREADY. This looked pretty good; it re-established her control of the NE corner, even extending it a bit. However, it failed to undo my NW corner foothold. This was a significant oversight in my view— and I quickly took advantage of it.

My opponent would have likely done better if she had played BLANDER. This would have had the added bonus of turning the N and L in my corner to red, forcing me to work much harder for a good reply move.

I played REBRANDS. This turned almost the entire top two rows to blue, including extending my dark blue squares from one to three. It also attacks the NE corner again. Overall, a very good move.

I was almost sure my opponent would come back with BRANDERS, using the exact same letters in a different word. However, since the SNR squares were now dark blue, playing them would not help her. As such, I thought I would still be ahead after the exchange. Not a great exchange for me, but the best I could see at the moment.

As it turned out, it didn’t matter, as my opponent played BLARED.

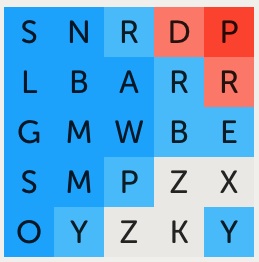

Moves 6-10. With BRAMBLED, MARBLED and MANGLED, we are pretty much treading water. I gain some traction with my move and my opponent reverses the gain with her move. When she played SPAMMED, I began to feel some additional heat (see figure). By moving into the southwest corner, especially by protecting the M, she was threatening to obtain control of the entire corner region. If she succeeded, she would almost certainly win the game. I was in trouble.

After much experimentation, I came up with SWORDPLAYERS. It accomplished my ongoing key goal of simultaneously attacking and defending. In particular, it protected the O (now dark blue) in the SW corner, thereby removing the danger at least for the moment.

Moves 11-15. My opponent came back strong with WORDPLAYS, using most of the letters I had just played. I returned the “favor” by playing SWORDPLAYS.

At this point, all the squares in the first two columns are blue except for the two M squares. If I could retain the eight blue squares plus add the two M squares, the entire first column would be protected (turn dark blue). More often than not, this translates into an unstoppable win. Would my opponent play a word that allowed me to do this?

She played BADGERS, an excellent comeback. It stopped me in my tracks. She attacked the G and S in the first column plus protected the M. Not at all what I was hoping to see.

I believed my opponent now had the lead. In fact, if it were possible to switch sides here and my opponent asked me to do so, I’d probably say yes.

The best I could think of for my next move was BADGES, duplicating the letters of her just-played word except for the R. For obvious reasons, I never like playing a word inferior to what my opponent just played. However, in this case, as all the R squares were either blue or dark red (protected), playing one of them would have made no difference in the position.

My opponent came back with BLADES. This was a huge error, in my view, because it left the first two columns exposed.

I believe my opponent would have done better had she replied with DEBAGS (using the same letters as BADGES) or even BARGED. Either of these would have kept an M protected.

As it stood, I at last had my chance to protect the entire first column — if I could come up with a word that used B, M, M and S.

Moves 16-20. At move 16, I played BAMMERS. I wasn’t even sure it was a word when I submitted it. But it is, because Letterpress accepted it. Bingo! For the first time, I had confidence that I would wind up winning the game. I would now be able to go on the attack more, with my opponent being on the defensive.

With BOMBARDERS, WARMONGERS, and SOMBER, we spent more time treading water. I tried to solidify and expand my western wall. My opponent tried to stop me.

At move 20, I had a major decision to make. I could have probably quickly finished and won the game, by playing a word like DAZZLERS. This would have turned both Z squares to blue and given me possession of the first three(!) columns. In retrospect, I believe I should have done exactly that.

However, I was greedy. I was now thinking not only about winning, but about winning with a crushing margin of victory (not very friendly, I know). So I instead went with ROBBERY. This turned every light red square on the board to blue, leaving my opponent with just the three (previously all dark) red squares in the NE corner. This seemed a potential crusher, but I was wrong.

By the way, I wasn’t worried about my opponent filling in the four unclaimed squares with a word that would end the game and give her a victory. I am almost certain that there isn’t any word that contains Z, Z, X, and K — certainly not one long enough to give my opponent a win. Having the unclaimed letters be uncommon ones was working to my advantage here.

Moves 21-25. With PASSERBY, my opponent gave me unanticipated trouble, causing me to regret my previous play. By turning the Y to red, my previously protected O in the SW corner was in jeopardy. My next word would need to include a Y, in order to re-protect the O. I had not expected this. So I played PANDERLY. With PRAYED, and BEARDY, we see-sawed again.

My opponent then gave up going after the Y square and played WORMED. I’m not certain whether this was a mistake or not. But it gave me the opportunity to go on the attack again.

Moves 26-30. I went with SWAMPED, bringing me back to about the same place I was after playing ROBBERY. My opponent played PREBOARDS, again leaving the Y untouched. I was now ready to pounce. I played ZAPPED, at last gaining possession of the three left columns.

If my opponent had any chance of winning, she lost it with SPARROW. With this word, she gave up control of the P in the NE corner, the location she had guarded since her very first move. Although there weren’t any great choices for her, this was perhaps the worst one. I can only assume the move was a mistake; she failed to see the consequences until after she had played. It happens.

I countered with WRAPPERS, leaving a score of 21-1.

Moves 31-end. The next several moves are relatively uninteresting — with the two of us exchanging similar words such as SWAMPY and SWAMPS. Essentially, I am jockeying for a maximum win position, while my opponent is trying to hang on to as many squares as she can. With BOXERS, I claimed the X. With MAWKS, I claimed the K. The game was about to end.

My opponent responded with WREAK. I was surprised. I thought she would play a word with Z, finishing the game even though she would lose. Instead, she left me to finish the game with BLAZERS — handing me a 22-3 victory.

Game 2

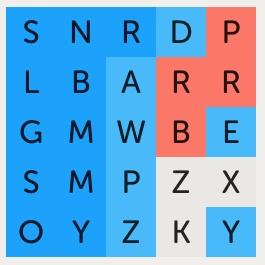

This second game demonstrates the same principles. Here, my opponent starts off with the NW corner and retains it till the end. I initially fight back by gaining control of the SW corner (see figure below). As the game develops, the outcome hinges on who will eventually possess the eastern end of the board. That turns out to be me, and I win 17-8.

Game 3

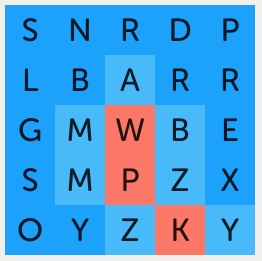

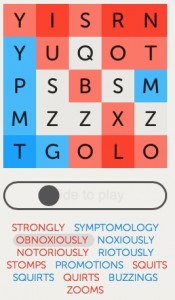

The third game is the shortest of the trio, lasting only thirteen (13) moves. Here, my opponent starts out with STRONGLY, grabbing the NE corner. She will never lose it. I thought I had a near-devastating first move reply with SYMPTOMOLOGY. However, she completely turned the game around with OBNOXIOUSLY (see figure below). Suddenly, I had the sinking feeling that the game might already be lost. Still, I fought on and came back with some good replies of my own. Despite some strong play from my opponent, I was able to secure a 16-9 win.

Bottom Line

Playing the longest word you can is typically a fine thing to do. Choosing a word that turns the most amount of your opponent’s squares to your color is often a better, quite excellent, thing to do. But neither of these things, by themselves, are sufficient to win consistently. I have seen many boards where one player owns almost all the currently claimed squares, yet winds up in a hopelessly lost position within the next move or two.

The key to winning is to figure out the strategically best squares to claim and figure out the word that best acquires them. In that regard, I often start a turn by selecting six or so squares that I would most like to acquire. I then see what words I can construct that include those letters. Take your time here. Don’t rush to make a move you will regret.

How do you know which are the best squares to claim? This requires an ability to look ahead and see the consequences of your move and the possible retaliatory consequences of your opponent’s next move. Hopefully, this article provides some insight on how to do this. I plan to write additional articles that explore this further, going back to some of the basics. Beyond that, the best way to learn is to play the game.