Apple’s new MacBook made an impressive debut at yesterday’s Apple Media Event. With features such as a 2304 x 1440 Retina display, Force Touch trackpad, and fanless design, it lives up to Apple’s billing as an innovative “reinvention” of a state-of-the-art laptop computer.

Still, despite dropping the Air suffix from its name, the new 12-inch laptop is a very close relative of the Air — both in appearance and target audience. On the other hand, the MacBook is so light (just two pounds) and so thin (24% thinner than an 11-inch MacBook Air) that its truest competitor may turn out to be the iPad Air rather than the MacBook Air.

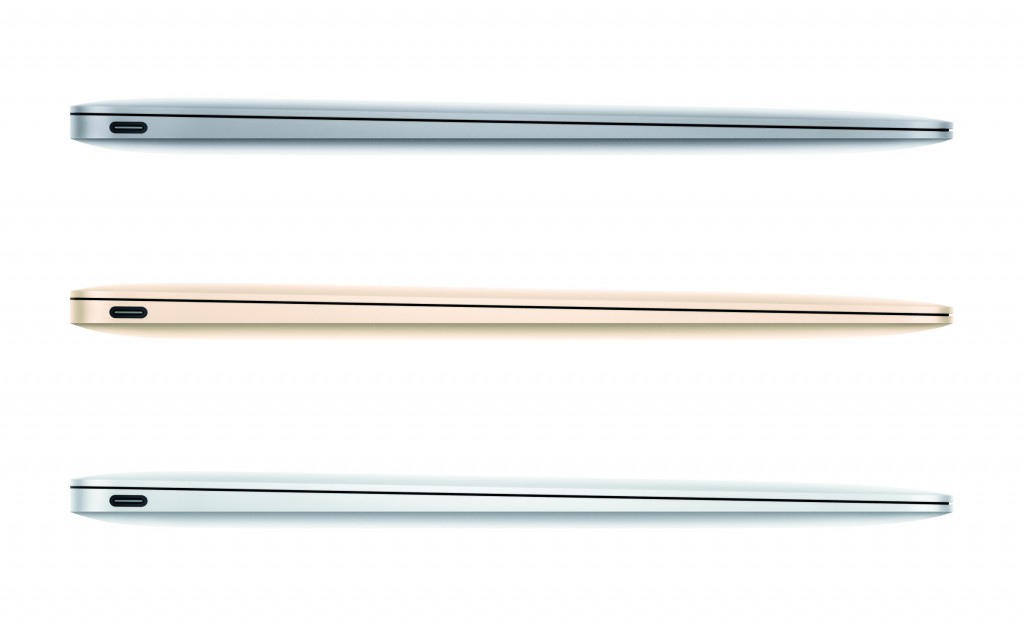

Reinforcing this iPad matchup, the new MacBook comes in the same assortment of three colors (silver, space gray and gold) as do Apple’s iPads. And (as with all iOS devices and unlike Apple’s other laptops), the new Macbook has no custom configuration options.

USB-C

There’s one more iPad similarity. And it’s a big one: The MacBook has only one port for wired connections (not counting an audio-out jack)! Really. Just one. That’s down from four (2 USB, 1 Thunderbolt, and a power port) in the MacBook Air. The new port even looks like an iOS Lightning port. But it’s not. It’s an entirely new, never-before-seen-on-an-Apple-device port called USB-C. This USB-C connection supports charging, USB 3.1 Gen 1 and DisplayPort 1.2. It does it all, as they say.

My first reaction to this news was: “What? Only one? Even if Apple wanted just one type of port, couldn’t they at least have included two of them?” That way you could charge a MacBook and have an external drive attached at the same time. As it now stands, unless you get an inevitable third-party USB-C hub, you can only do one of these things at a time.

And no Thunderbolt? This means you can’t connect a MacBook to Apple’s Thunderbolt display — an option that had been strongly promoted by Apple just a couple of year’s ago.

I was ready to conclude this whole USB-C thing was a serious misstep on Apple’s part. And it may yet prove to be so. But, more likely, it is Apple once again staying ahead of the curve, pushing the envelope, or whatever similar analogy you prefer. Remember when the iMac first came out, without any floppy drive? People said it was a huge mistake. But it turned out to be prescient. This is Apple doing the same thing.

First, given the target audience for this Mac, which is the low end of the market, the limitations of a lone USB-C port are likely to be less than they may appear. For example, prospective MacBook owners are not the sort to purchase a Thunderbolt Display. That’s more for the MacBook Pro crowd.

More importantly, with the new MacBook, Apple is pushing us towards a world when all connections will be wireless — either to other local wireless devices or over the Internet to the cloud. Want to back up your MacBook? Connect it wirelessly to a Time Capsule. Want a larger display? Use AirPlay to mirror your display to a television. Want to store your super-large music and photo libraries? Use iCloud.

iPad Pro?

Let’s return to the iPad/MacBook similarity. Rumors continue to circulate that Apple will be releasing a 12-inch iPad Pro later this year. Does such a device still make sense, given the arrival of this new MacBook?

Personally, I much prefer an iPad to a laptop for many tasks. There are many times when I find iOS apps and a touchscreen more convenient and more practical than Mac app alternatives and an intrusive physical keyboard. Want to read the New York Times, check the weather, read a Kindle book, play a game, listen to a podcast? The iPad is the better choice. When I am home, I use my iPad Air almost exclusively, while my MacBook Pro gathers dust (I have a desktop Mac for tasks that the Air doesn’t handle well).

The iPad Air also beats even this latest MacBook in terms of weight and size — by a wide margin: the iPad is half the weight and almost half the thickness of the MacBook.

Overall, I don’t see the new MacBook significantly affecting sales of the iPad Air or mini.

A supposed iPad Pro is a different story. An iPad Pro will presumably be targeted for “productivity” tasks that are the traditional domain of laptops — tasks where you typically prefer a physical keyboard. The new MacBook will give an iPad Pro a run for its money here. Even if you could “get by” with just an iPad Pro, a MacBook (with the more powerful and flexible OS X) will be the better choice for getting work done.

Bottom line: Many people will still prefer to own some combination of iOS device(s) and Mac(s). I certainly will. But it’s hard to imagine users opting for both a new MacBook and an iPad Pro. It will be one or the other. And the new MacBook is more likely to be the winner. That’s why I am beginning to have serious doubts about the viability of an iPad Pro. The new MacBook may kill the device before it’s even born.

One final thought: If an iPad Pro is coming…might it come with a USB-C port instead of (or more likely in addition to) a Lightning port? If so, this would allow the Pro to offer an assortment of productivity options not currently possible with existing iPads.