It’s the sad end to a glorious era. Macworld magazine is dead. Over. Kaput.

The next print issue of Macworld will be the last.

But that’s not what is truly sad. Or surprising. The demise of Macworld’s print magazine has been expected for several years. Almost all other technology print publications, including Macworld’s PCWorld sibling, have already vanished. There was no way they could compete with the immediacy, ubiquity and free availability of the web. Macworld has now joined their ranks.

Macworld intends to continue as the macworld.com website. As this is where most Macworld readers were already consuming the content, the transition need not have been a traumatic one. But it is.

This is because, in addition to ceasing print publication, Macworld laid off almost its entire editorial staff. This is not an exaggeration. Dan Frakes, Dan Moren, Dan Miller, Phil Michaels, Serenity Caldwell (correction: Serenity resigned a few days previously; I have heard that she would have otherwise been retained), and Jason Snell (technically, Jason had planned to quit before he could be laid off, but the end result is the same). They are all gone — as are several others that I do not know as well. It is the end of the line for the greatest bunch of people I’ve ever had the privilege to work with. Only Chris Breen appears to have survived. He must be checking his shirt for bullet holes about now, wondering how he could be the only one left standing after the massacre.

After recovering from the shock of this news, my first question was: How can Macworld continue as a website? Who will be left to write the stories? Who will be left to manage the site? I’ve been told that a skeleton crew, perhaps headed by Chris, will attempt the job. There will be an increased dependence on freelance writers (disclaimer: I have already been approached in this regard). While this will assuredly save Macworld money, they will be losing the critical commitment of a full-time staff.

The focus of and range of topics covered by Macworld will inevitably narrow. But they intend to soldier on.

I wish them well. Truly. Still, in my heart, I feel like the Macworld I have known for three decades has effectively ended. It was the people who made Macworld great. And those people are gone. To be frank, I won’t be surprised if, within a year, the site has either vanished or morphed into something that is no longer recognizable.

Looking back

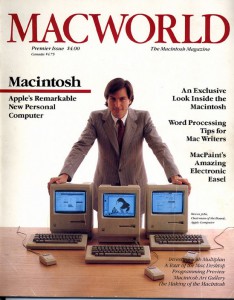

Macworld holds a special spot in the history of Apple and the Mac. It was the very first Mac-only publication, premiering in January 1984, simultaneously with the Mac itself (I still have a copy of every issue!). It outlasted numerous competitors, including MacUser (whose demise is what led me to become a writer for Macworld). It quickly attained and maintained a position as the #1 most respected and authoritative publication for everything Apple. I’ve been proud to be listed on its masthead.

With the rise of the web years ago, Macworld had to struggle to adjust. I give Jason Snell the lion’s share of the credit for successfully navigating the transition. Before he took over as editor, macworld.com was just a weak extension of the print magazine. Its content was largely limited to web translations of print articles. Even here, you had to wait about a month after an issue appeared on newsstands before those articles showed up on the website. Given the fast pace of the web, this was a recipe for disaster.

Jason turned Macworld around, making the website its focus. Everything appeared first on the web, typically within hours of breaking news. The print magazine became a curated version of what had appeared on the web in the previous weeks. It worked. I believe this probably saved Macworld from going under years ago.

Along the way, Jason assembled what became one of the best teams in tech journalism. That’s why it was heart-breaking to witness the near total collapse that occurred yesterday. I can only hope that the people laid off find other satisfying work very soon.

It is the way of the world today that people move on to the next thing at nearly light-speed. The 24-hour news cycle demands it. So I expect that, for most people, the news of the “demise” of Macworld will soon be barely a memory. Like the people at the end of The Truman Show movie, people will shrug their shoulders and ask “What else is on?” It’s inevitable.

For me, however, the aftershocks of this event will linger for quite some time. Perhaps it’s because I’m closer to the epicenter. Regardless, there’s been a shift in the ground beneath me. It will be long while before it all settles again.